An Unsung Masterpiece in Wychwood Park

Architect Ian MacDonald’s house taps into powerful collective myths

Like Jonas Salk, who shot his newly invented polio vaccine into his own arm and the arms of his children, architects sometimes experiment on themselves. What choice do they have? Clients don’t like being treated as test subjects. So, when architects wish to work through their most creative ideas, they must do it on their own dime.

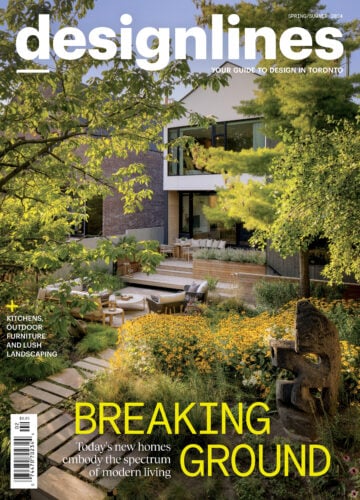

Toronto’s Ian MacDonald is an architects’ architect. He’s not as well-known as his most famous Canadian peers, but those peers all admire him. His house in Toronto’s Wychwood Park neighbourhood, which he shares with his wife, is surely his masterwork. It has graced magazine covers and won all the big prizes—a Canadian Architect Award, a Governor General’s Medal. But for the general public, it remains a secret.

It is, quite literally, hard to find. Years ago, having been told about the house by the architect Nova Tayona, a former student of MacDonald’s, I went searching for it among the Arts and Crafts mansions of Wychwood, with their wrought iron and stained glass and asymmetrical gables. MacDonald’s house is less ostentatious than anything around it. It appears from the outside like a rectangular bungalow, obscured by foliage. “Ian has an ethic of neighbourliness,” says Tayona. “He wanted to do something modern, but without undermining the historic character of the community.”

I located the house eventually. From then on, every time I found myself near Wychwood, I’d drop by and trespass on the property. One day, thanks to a press contact, I got invited in. Although really, I should say “invited down,” since most of the home sits a full storey below grade. “The house is like an iceberg,” says MacDonald. “Most of its volume and liveable spaces are below the original grade.”

When MacDonald bought the property in the mid 1990s—a narrow, triangular lot, with a dilapidated bungalow—it was the farthest thing from promising. But these days, subpar properties are the only kind that normal people can afford. And anyway, MacDonald likes a challenge.

He has always viewed architecture as an optimization problem: the goal is to transcend the limitations that a given site imposes. In his projects, he often uses clever fenestration and optical illusions. If there’s a road positioned in otherwise pristine wilderness, he’ll set a window at exactly the right spot to erase the middle distance. He uses glazing for a variety of purposes, differentiating between “light windows,” which can be clerestories or skylights, and “view windows,” which frame the outdoors. He’ll set windows at floor level or inside bookcases if he feels there’s something there to see—and he’ll position them at the ends of narrow corridors to enhance the sense of depth. You can’t fully control what a property looks like, he reasons, but you can decide what you do with it—and what you focus on.

At Wychwood, due heritage designations, MacDonald had to treat the original bungalow with a degree of deference: any updates had to do honour to its modernist character. Neighbours opposed above-grade additions, because they didn’t want to obstruct views onto the historic house of Marmaduke Matthews, a Victorian-era painter and the founder of Wychwood Park. Given those constraints, the only viable way for MacDonald to add space was to go downward.

He carved out what was effectively a second lot within the larger one, a rectangular pit, fortified with retaining walls. The public spaces of the house—a Jatoba-clad living area, a carpeted den and a kitchen between them—are inside this earthen container, in the bottom half of the building. I hesitate to call it the “basement,” because that word doesn’t come close to describing the vibe.

The rooms feel more sunken than subterranean. The living room steps out onto a recessed courtyard. The den has high clerestory apertures that sit just above grade. Running lengthwise along the west side of the home, there’s a double-height space with millwork benches, a stairway leading up to the ground-level sleeping quarters, and expansive windows looking out onto a sandstone retaining wall. “I picked sandstone,” says MacDonald, “because it has the perfect pH levels and porosity for moss.”

I could gush about the home’s other, more conventional architectural features: the narrow passageways that dramatically open onto larger voids; the planar landings, benches, and raised floors that bring volumetric complexity to the rooms; and the tactile materials, from concrete to wood paneling, so beloved of mid-century architects in places like Palm Springs or New Canaan. But it’s the subterranean elements that elevate the house (if you’ll forgive the awkward verb) from merely good to spectacular. “It’s like land art,” says Brigitte Shim, co-founder of the legendary Toronto firm Shim-Sutcliffe. Shim admires its nuanced approach to context. For her, the home feels heroic, almost geological. Normally, if you’re building a modern house in a heritage neighbourhood, you would add a gable as an ersatz concession to local vernacular. “That approach is, for me, disingenuous,” says Shim. She prefers MacDonald’s MO: to discreetly eschew old-timey gimmicks and go all in on modernism.

For Brian MacKay-Lyons, the celebrated Nova Scotia architect, MacDonald’s house derives its appeal from the way it taps into Jungian architypes—myths that are so ubiquitous they seem imbedded in our collective unconscious. For him, the project evokes the inventor Rotwang’s house in Fritz Lang’s silent-era classic Metropolis, a woodsy cottage that is also a portal into a vast subterranean world. “That’s a classic theme,” says MacKay-Lyons “the cottage in the woods, where you open a trap door and find something else underneath.” The surprise, in MacDonald’s case, is that the subterrain lair isn’t sinister but welcoming.

In the 20 years Ian MacDonald has lived in his home, he’s found the Wychwood soil to be a gracious host. The retaining walls protect privacy and filter light, despite the expansive windows. And because the house is largely underground, it naturally stays cool in summer and warm in winter. “My energy bills are surprisingly low,” says MacDonald. To enter the house is to descend into a kind of underworld, not Hades and certainly not Hell, but simply the Earth—our Earth, which loves us and cares for us and will offer us all a final home eventually.